Texts

Animal Kingdom

Written by MILENA ESTRADA and published on June 20th, 2019 in Yet Another Art Blog

The animal kingdom as we conceive it in our liberal, cosummerist minds is a perpetual competition between one another, an unforgiven fight to stay at the top of the chain. This is how we have managed to justify our barbarous behaviour towards other species, the environment or even among ourselves.

Instead of interrogating over and over again the human condition, the Italian painter Lorella Paleni shifts her attention to animals in an effort to show the similarities we share with them, evincing once and for all that what we assume to be “animal behaviour” is a biased interpretation of otherness.

Gilles Deleuze in his book Francis Bacon: Logic of Sensation speaks about what makes Bacon’s characters so akin to animals. According to the philosopher, in Bacon’s work, there’s what he calls a “zone of indiscernibility” where man becomes an animal and the animal transforms into man’s mind. The face is replaced by a stroke, there’s no way to discern the nature of what we see, except that it is flesh. In Lorella Paleni paintings the human face is completely devoid of any features. In her series Sleepwalkers the characters have blurry faces or just melt with the rest of the composition. Animals on the other hand possess neat faces and may look straight at us like the monkeys in her series Dwellers. “I feel drawn to animals because of their uncanny similarities with the human and the way we tend to look at them. Because a lot of my work, when I deal with animals, has to do with the animal gaze and with meeting this other being as a being per se and not as an object.” The meeting point is indeed the face, more specifically the eyes, the windows through which we recognize ourselves in others.

This takes us to the Anthropocene, the so called new geological era where humans have triggered the current climate crisis having obliged us to see beyond to assess the impact of exploiting the earth. It is more and more common to see creators turn their attention to other species to decolonize our gaze. Jacov Von Uexküll in his book A Foray into the world of animals and humans: with a theory of meaning introduced his readers to what he called “umwelt”, a concept explaining that living beings perceive the world through a subjective perspective influenced by the environment surrounding them, each way of seeing the world is different for each species. Paleni’s work seems to take this into account as she creates environments where animals live in a different time-space zone, we share our existence with them but communicate with them not via a specific language but through the body or the relationships we develop with them. “With a lot of other representations of animals, they’re often not subjects, they’re objects. Even historically in painting, which is very similar in the case of women, women are represented like a body to please, their body is seen through the male gaze … Animals, they are disposable, they represent something else, an allegory of something but they never are subjects themselves or very rarely so I was interested in them as subjects.”

Another of the themes recently examined by Paleni are women and how we are represented. For a series of portraits she still is working on she took inspiration in the figure of the witch as conceived in the Middle Ages: “I was reading about these women and I found a book written by an Italian writer that collected the documents of the processes with names and the written words of the women, the tortures they endured… Initially I wasn’t planning to do any series but my readings lead to a quest. Most of these women were poor women, there are no representations of them, there are no portraits, they were forgotten in a way. I found there was a connection, all this history resonated somehow so I decided to make portraits of them using the portraits of friends.” Portraits throughout history have been tools used to strengthen and evince power, during the Renaissance and the 19th century only wealthy families could afford to be painted by artists. By focusing on animals and women, Paleni’s work introduces to painting not dominant males but fragile and vulnerable beings giving them a place in art history.

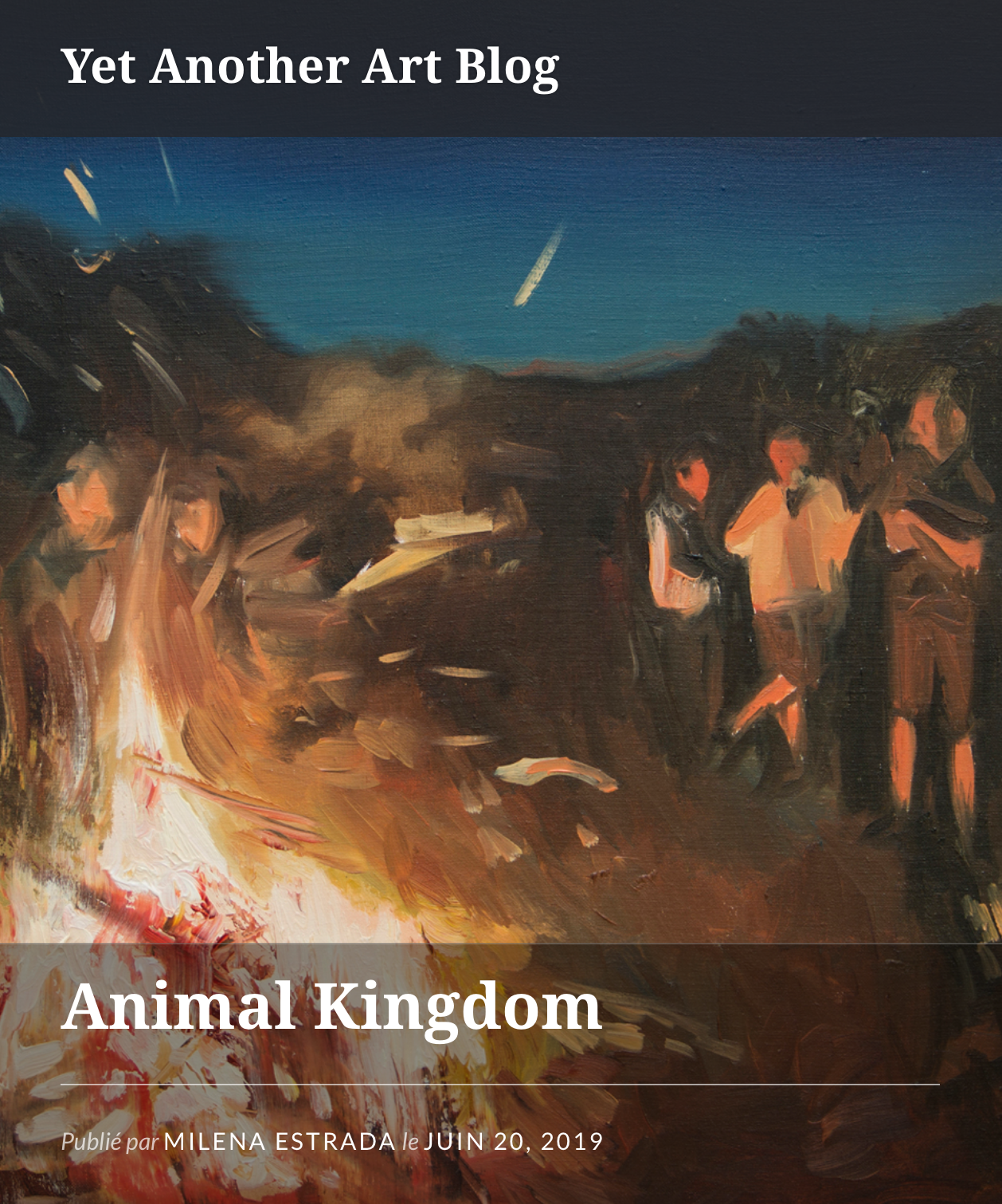

In terms of aesthetics, a recurrent leitmotiv in the artist’s body of work is fire. Series such as Dwellers, Otherwise or Dusks-s are abundant with characters wrapped in flames or standing by the fire. The element can be decoded as assembling as well as tearing apart or destroying. Moreover, rituals and pagan gatherings come to mind as we observe the artist’s paintings, fire is a force that united people in the Middle Ages. As stated by the artist, fires and ceremonies were a space where people could assemble, discuss about politics and resist. In her canvas The Ritual 2 the colours and the light beaming on it are what lures us to the action. “To me the colours come from a feeling, I try to use feelings to build my paintings (…) This is why I don’t want my paintings to be descriptive, I want to have a conversation with the viewers rather than to say a story”. This could be why her creations are so similar to paintings by surrealists like Remedios Varo or Dorothea Tanning were the viewer is in a hazy zone, a purgatory with flimsy spirits. Nevertheless, Paleni seems to push further by constructing a pictorial space where abstraction and the material world join together in an entangled oil mesh. It’s not always easy to discern what’s happening inside the canvas leaving the spectator’s mind run amok. The assembling is done little by little enabling the painting to take shape like a living organism. Accidents are not excluded, they can happen but are regarded as part of the creative process. “When I start the work, I rarely know what it’s going to be. The process, my interaction with the canvas and with the painting it’s essential for me and is almost by ‘chance’ that things happen. There’s almost like a sort of conversation happening between me and the medium where it’s not only me deliberately painting the image but I’m also responding to what’s happening on the canvas.”

Despite not being political at first sight, Lorella Paleni’s paintings unbosom as subtle statements on women’s position, animals and the Anthropocene as well as painting itself. Nostalgic at times, Paleni’s compositions zones of indiscernibility connecting us with the animal kingdom and bringing us closer to unexplored layers of our existence.

Excerpt from “Listening to the Anthropocene” Essay by Douglas Cushing

published in occasion of the exhibition "Listening to the Anthropocene", curated by Douglas Cushing at the Sarofim Fine Arts Gallery and in connection with the 2019 Brown Symposium.

Full essay here.

“ Lorella Paleni’s canvases are richly painted spaces of dialogue as well as sites of ambivalence where we struggle to reconcile our existence with that of non-human nature. They are liminal zones of contact or gap between human and animal spheres of comprehensibility. By extension, these paintings’ leitmotif is also relationships broadly, particularly between privileged parties and their others. Paleni’s paintings act as curious mirrors where animals sometimes appear as inscrutable phantoms of the real beyond our reach, and elsewhere we seem to be ghosts intruding upon their world. Translation or failure to translate—an inability to assimilate all that always exceeds the translation— drives one’s encounter with Paleni’s works. Failure to translate does not imply a lack of meaning. Rather it highlights issues of mishearing, incompatibility of apprehensive frameworks, disparity of value systems, and the limitations of human cognition. In Paleni’s paintings, we grope about in the dark, and in our groping the myth of human mastery falters.

Galileo Galilei, Paleni’s compatriot of centuries past, once claimed, “Philosophy is a great book, which remains open to our gaze (I mean the Universe), but we cannot grasp it unless we first understand its language and are familiar with its characters.” Mathematics, he insisted, constituted that language and geometry its symbols. His meaning is plain, but his assertion also points, conversely, to the limits of natural philosophy. For such systems, the unquantifiable is inadmissible. In so far as experience (human and non-human) overflows the metrics applied to it, it verges upon meaninglessness. This is not to say that the somatic functions accompanying experience are immensurable. Rather, such observations are limited to describing the material conditions of a state rather than the gestalt of the state itself. By contrast, while art may also traffic in rational concepts and empirical observations, it additionally admits the superabundance of experience that escapes logical systems. This includes all that is indeterminate, unknowable, or felt. This is art’s poetic dimension. Rhetorical devices and figures (metaphor, synecdoche, metonymy, symbolism, etcetera) and the abstract associations and affects accompanying formal qualities such as form, color, and line permit direct and indirect access to that which stands outside the rational frame. Paleni’s work finds a footing in addressing human-animal coexistence with just such an amalgam of observation and visual poetics.

Within Unruly and Guests, form dissipates, solidifies, falls into foliate darkness, and emerges again into the light. Plane and line are interwoven like textile and imbricated like scales. Forms flow into one another, even when divided by line: surface color and texture breach such boundaries. Space vacillates between flat, painterly superficiality and naturalistic illusion–between surface and depth. Here is a complex weave of figure and ground, of light and dark, of positive and negative space. Consider the macaque positioned at the top left of Unruly. Outlined in dark browns, its body reveals a thin layer of warm blues and greens throughout–suggesting sky and verdant brush. Figure and ground are dynamic: collapsing into one another, intermingling, and thrusting themselves apart again. Looking at the top-left quadrant of the canvas, the animal’s head and face— with reddish skin partially framed by light grey wisps of hair—compete with apparitions of dark vegetation for a space just behind the pictorial plane. Compared to the warmer regions of the painting’s bottom right, however, this macaque and its surroundings fall back and begin to dissolve. But seen in isolation again, its right eye and muzzle materialize from these depths, drawing its ephemeral body up with it. Paint is applied in thin layers, impastos, and glazes; it is scratched into, scraped away, and built up again forming a palimpsest of frustrated communications–forays and retreats in a quest to connect. These works are metaphorical looms for material and immaterial forms.

Macaques’ faces emerge from the canvas’ surfaces, some conspicuous, others reluctant to appear. Some return the viewer’s gaze, bold and confrontational. Some steal furtive looks from the depths. Others take no notice. There is a marked vacillation in the gaze returned to us by these beings. It seems to hover between opacity, reticence, and sympathetic exchange (meant here in the sense of “feeling together”). This gaze is markedly uncanny. Might we still retain some latent, primate memory held in common with these close relatives? We search ourselves for ourselves. We search in ourselves for them. We observe ourselves being observed in the eyes of the other. We want to know how they regard us, but we cannot know. We discover a gap, a lack in ourselves.

We are drawn to these faces, but do we address them as individual beings? If not, what must we escape in order to do so? In his book The Gay Science, Friedrich Nietzsche argues that human logic was born from an initial illogic. “As regards both nourishment and hostile animals,” he writes, survival favored those who treated “as equal what is merely similar.” Thus, human logic assumes a categorical mode of thinking in which our first impulse is to flatten groups of disparate entities, dismissing the particularity of individual members. It is easy to relate to the macaques in Paleni’s paintings in a single, uniform fashion, to collectively name them “macaques,” classing them as one thing and ending the matter. Alternately, however, without anthropomorphizing, we could admit that the macaques’ expressions and attentions differ widely. Unruly and Guests plead with us to address each animal as a unique subject with its own mode of being in the world.

After their faces, we notice the macaques’ hands: organs of touch, grasp, and embrace. Hands seem so familiar to us, even the hands of another. We are prompted to empathize, but if we do, we find ourselves adrift in speculation. What is it to be each of these creatures? What part of their existence lies beyond what I can know? How does my misunderstanding of them shape my interactions with them? How do such miscommunications and misapprehensions shape our attitude towards the whole world? Locke’s theory of property and economy, and ideas descending from it, have long justified the “pasturage, tillage, or planting” of formerly wild lands in order to serve the free market. As our species continues to alter these lands, we find ourselves in increasingly close contact with wildlife that we do not understand as beings. We regard them as mere things. We invade their homes and displace them. These meetings—these episodes of violence—additionally produce new disease vectors affecting our species as well in the process, e.g., HIV, malaria, etcetera. Yet we seem willfully blind to the connection between our self-inflicted damage and the harm we afford to these animal others. All the marketplace asks of us in exchange for progress, it seems, is our sight.

Paleni’s I’ll Drown is an unnerving work. A large, palely painted marine mammal lay upon a table with raised sides. A group of humans position themselves at either side of the creature, making physical contact with it. They seem to be in the middle of a disappearing act, however; they are becoming air-thin, ghostly before our eyes. All that seems concrete of them is their aprons and gloves. The viewer’s eye is drawn to the three blue gloves just above the heart of the canvas. They form a triangle. The yellow aprons, the corner of the table, and wedges of floor constitute more triangles. Paleni uses these groups of interlocked triangles to compose her painting in a noticeably academic manner. They lend structure and keep the eye moving predictably. This rational order stands as counterweight to the work’s ultimate ambivalence, a structural bulwark against instability of the painting’s semantics.

Gloved hands make contact at various points along the creature’s body. The purpose of this touch, however, is unclear. Are these people harming the creature? Is it dying or already dead? Are they attempting to save or heal it? Does the creature lie upon a dissecting surface or an operating table? The scene refuses clear answers. It resists our desire for surety. Paleni writes of her art, “ There is also, however, an alchemy to this painting that transmutes human action into something absolutely foreign and unknowable. We are othered for ourselves and simultaneously invited to explore beyond ourselves. In engaging with such open spaces, we welcome conversations with all those we have pushed away in the course ofmanufacturing the Anthropocene. Even as we have physically insinuated our species into every corner of the planet, we have paradoxically walled ourselves off from nature in our ideas and attitudes. For the sake of our species, and for that of all the other beings with whom we share this planet, we can no longer afford to erect such walls. “

Flashes in the Breach by Natasha Marie Llorens

Flashes in the Breach

Light hitting industrial aprons, bright yellow. Blood, but faded. Aging blood, dusty red. Thick latex gloves, the same shade as those used for human surgery. A light blue, but one that is sure of itself. Paleni’s colors are accents against a wash of grey. The object of her painting, I’ll drown (2015), is a creature that is dissipating quickly into a shadow of itself. The caudal fin of a giant fish is the most precisely rendered object in the work and it is slumping off the edge of a gutting table. The creature is a luminous grey, a great curved body that decisive but tiny hands have already grasped with propriety.

I’ll drown is a portrait of death. The ones who will manage the aftermath of the body are alert to the tasks that lay before them. Blue fingers frame a triangle in the center of the canvas, pushing and grasping. They are unified in movement. They need to catch the freshness, the aliveness. They need to work quickly. The shimmer behind them, running down the right side of the painting, is a reminder that this event is nevertheless a breach. A consciousness has been displaced from the thick, inert mass to some space outside of the movements of these faceless people and their mandate. The shimmer breaks up the representation of a solid grey floor, dispersing the very pictorial illusion of space that these bodies and their management of death occupy so unselfconsciously.

Ghost Dog’s background tones could have been borrowed from 19th Century American painting. Somber greens and muddy, rich browns. Indistinct foliage, undisciplined by fastidious old-world gardeners. The space suggests a clearing in some landscape of mature brush. There might be brook rushing through a break in the leaves on the left, or else it is only a cool shadow. The point of this setting—as it is in much 19th Century American painting—is that some event is taking place in Nature, which is defined as a mysterious place that nevertheless remains frame-able, knowable to a viewer.

The human is a slender sketch with one hip thrown out and one foot elegantly pointed in the dust. He throws a straight shadow that is unwavering on the ground behind his unshod feet. The bear is richly clothed in locks of fur, a crescent-shaped streak of pale marking the breast like an elaborate indigenous necklace. She is alive whereas he is abstract. It would be a mistake to be seduced by the bared claws, by the howling mouth rendered as a smudge of red, or by her apparent strength and balance on hind legs. No animal fury will free this being from her pair, just as there is no actual wilderness in the background to lope towards. The event of the painting is subjugation accomplished.

It is as though the human were demonstrating how a vivid, furious existence could be so completely mastered by a casually posed, barely embodied human being. His body paired with hers. The space between them, full of her sound and his silence, is tense but it is also absent of movement. This human has no need of language. Subjugation in this scene is not about a command called out and then obeyed. What is passing between the human and the bear is gestural: a strap disappearing into her face, her right paw curled in towards her chest, his left hand raised and held menacingly but lightly above his head. Each is locked into their own, and visually distinct, aesthetic experience of the same instant. Each is adorned with symbolic gestures of the roles they are to play in this masquerade of an encounter between the human and the animal.

A tangle of forms obscures the top half of Paleni’s painting Man’s Will (2017). Feathers, antlers, ochre-colored frock sleeves, leafy branches, and a single yellow eye in the center of the composition dispassionately overseeing the operation underway in the foreground. The profuse composition is standard in Paleni’s work, signifying the chaotic unknowability of the natural world. An uncanny density marks the light that filters through this mass of formal layers. It is as though the outside layer of foliage was dancing in the morning light, whereas the mess of shirt sleeves and feathers and fallen leaves in the center of the painting were in a different time, late into an autumn afternoon. Even before the viewer’s eye reaches the hands and tries to discern the nature of the operation in which they are engaged, the painting is already a record of disjuncture and irreconcilable juxtaposition.

Put differently, it is not the fact that hands dismiss everything except the disassembled crocodile that is striking in Man’s Will, but rather the fact that these worlds manage to exist together on the same representational surface. The hands are gloved. The muscles and tendons of their wrists and knuckles are muted by a light fabric, which could be latex or its thick rubber precursor. They are also clean of stains from whatever it is that they are doing to the face of the crocodile that lays beneath them. Their task is not urgent—they are not saving a life or trying to package it quickly enough that humans can benefit from life’s proximity. The crocodile is being very carefully disfigured so as not to mar its skin, which will be used, perhaps, for handbags or luxury high-heeled shoes.

The hands and their instruments are a visual echo of the shape and density of the crocodile’s teeth. These lurk inactive at the bottom of the canvas, as though waiting for the creature’s vision to be restored before coming to life to tear fingers from wrists. The hands and the teeth are thus similar objects from incommensurable paradigms for incision. The event here is the lack of reciprocity between the universe of the hands, and of their scalpels, and the universe of the motionless reptile, with its beautiful teeth.

Paleni’s work is concerned with the process by which the animal becomes incorporated into a human system of value and consumption at the expense of the being that was once irreconcilably unknowable to the human. She paints the threshold between the animal—in itself, as a consciousness whose perspective can only ever be imagined—and what humans make of this being.

Jacques Derrida wrote about a similar threshold in The Animal That Therefore I Am. The philosopher describes finding himself naked and observed by a specific, very small, cat, which he is careful to stress is not metaphorical. When he understands that he is observing a being without access to language that is in the act of observing him—Jacques Derrida, the naked man, slowly aging and in his bathroom—he understands that language as a system is organized to exclude the impossible unknowability of just such an encounter. As a system, logos is organized to justify man’s lack of responsibility to those beings with which it cannot have a legible relationship, beings that cannot be contained by the sense the word makes of the world.

The great fish cannot, in language, lament the loss of the vast, cold, darkness of the ocean’s depths and so its loss falls outside the purview of man’s responsibility, and also falls outside of justice. The bear’s fury is not reasoned, is not politely argued as a loss of life and liberty and the destruction of an ancestral home at the hands of shallow adventure capitalists. There is no precedent to justify her right to unqualified freedom of movement. There is no way to know in semiotic terms what the crocodile might once have thought of the beings that now carefully place their scalpels into its head, and so the question of its experience of the world and of the value it places on its own skin is an unsolvable enigma, which is therefore dismissible as non-sense.

Derrida’s point is that humans do not, in fact, allow themselves to recognize the encounter between humans and animals for what it is: a limit to the system according to which they have organized the whole world. Paleni’s paintings also abut this limit. They are not really representations of violence done to animals. They are, rather, images of disjuncture between the existence of the animal and the existence of the human animal. They are an attempt to represent the impossibility of an encounter in language, like flashes in the breach between the cat and her philosopher.

The Creators Project on Vice, Words by Andrew Nunes

Humans Ain't Nothin' But Mammals in these Animalistic Paintings

Lorella Paleni's zoomorphic portraits reflect the brutality of everyday human life.

Nov 29 2016, 4:41pm

It isn’t news that animals are complex creatures, capable of many things assumed to be inherently human, ranging from the ability to learn language to the capacity of feeling a spectrum of emotions. But rather than examining how animals are human-like, Italian painter Lorella Paleni makes work that focuses on how humans can often act in ways that are incredibly animalistic, bridging the gap between animals and people in a way that opposes this popular, overarching narrative.

In Mishap 7, a painting belonging to a series of works Paleni labels as “small playground spaces,” an entanglement of human limbs bleeds into what appears to be a neon body of water. The flailing legs and arms are contorted dramatically and abstractly, hovering somewhere between a fight to the death and pool party shenanigans. Perhaps the two are not so different in the end.

Similarly, I’ll drown shows shadowy human figures appearing to be rescuing or operating on a bleeding shark or small whale. Their philanthropic gestures end up looking more like an assault on the creature, violently pushing and pulling as if exerting dominance or control over its lifeless body.

Paleni’s ability to make a seemingly humane activity look like a pagan ritual exemplifies the overarching philosophy of her work: “I think and see animals like equal fellows, companions of a shared journey. Humane society is built on the refusal of the other’s value in order to create a hierarchic system that favors the few; the animal is the quintessential ‘other’,” the artist explains to The Creators Project.

“The animal questions us about our own humanity, about who and what we are, and the validity of language. We share a common destiny, as animals. As Elizabeth Grosz said ‘Man is not the center of animal life, just as Earth is not the center of the universe.”

Even the artist’s approach to bridging the gap between animal and human is reflective of her philosophy. “Rather than anthropomorphizing the animal (which is still a way of stating the importance of the human and the need for the animal to be humanized, filling an alleged lack), I’m interested in animalizing the human. Refusing the traditional ‘portrait’ is a way for me to question that, to question subjectivity and human exceptionalism,” adds Paleni.

Article

Mishap 7, Lorella Paleni, 2015

Da Bergamo a New York con i pennelli in tasca

Simone Dumdam

22/01/2016

29 anni, bergamasca, un diploma all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Venezia, un Master in Arti Visive alla Columbia University di New York; i suoi lavori sono stati presentati in esposizioni in diverse città fra cui New York, Berlino, Milano, Londra, Venezia e Kaunas. È una degli artisti nominati nel 2015 per la Rema Hort Mann Foundation Grant di New York, dove vive e lavora da qualche anno. Questa è Lorella Paleni, pittrice; un’italiana a New York. Insegue i suoi sogni e le sue aspirazioni da sempre e colpisce nel segno quando mi dice che “Ogni giorno ti svegli e ti dici che questo è ciò che vuoi fare”. Un esempio per quanti vogliano fare della propria passione e talento il loro mestiere.

Di Lorella sorprendono il carattere forte e determinato, l’estrema sensibilità e naturalmente un talento innato che le sta dando molte soddisfazioni, non solo come pittrice ma anche con le sue stupende video animazioni

A questo punto la domanda è d’obbligo: è stata valorizzata maggiormente all’estero rispetto al suo Paese d’origine? E perché?

“Siamo un paese – l’Italia – estremamente legato alle tradizioni e alle abitudini, con una gran paura del cambiamento e del mettersi in gioco. E credo sinceramente che ci sia anche un grosso problema di nepotismo che possiamo vedere ovunque, non solo nel campo delle arti. NY è una città estremamente stimolante e ricca per un creativo, cosi come lo è Berlino che anche amo”.

Ha girato molto, è un continuo divenire, sempre alla ricerca di una nuova scoperta; nessuna verità assoluta, quindi. Le sue opere, infatti, dicono soprattutto questo…

“Non penso a nessuno dei miei lavori come a una descrizione, piuttosto come riflessione, e come tali non credo siano rappresentazione fedele di una realtà esterna, di una verità che infatti non credo esista in senso universale. Quello che spero che le mie opere facciano è presentare se stesse come quello che sono: un processo di scoperta, una serie di domande che portano ad altre domande”.

Un processo di maturazione, di evoluzione. Una visione della realtà che corrisponde appieno al periodo storico che stiamo vivendo. La ricerca della novità, attraversare la superficie per giungere alla profondità. Nella società odierna che scorre in fretta a volte manca proprio il concetto di riflessione, di porsi domande e fermarsi a pensare. Oggi raramente ci si prende una pausa per chiedersi dove porterà quello che si sta facendo.

Lorella si pone ogni volta delle domande, una sua peculiarità, unitamente ad una curiositas che la porta di volta in volta a scoprire nuove sensazioni e visioni…

“Quando realizzo un’opera non penso a cosa quel dipinto, disegno o animazione sarà al suo completamento, ma a cosa posso scoprire nel processo del fare. Penso al fare arte come a un fare ricerca che funziona attraverso canali differenti. In parallelo col fare c’è tanto leggere, ricercare e chiedersi, soprattutto”

Il messaggio che vorrebbe arrivasse è proprio basato sul concetto di scoperta e di stimolo per lo spettatore:

“Vorrei che gli spettatori rimanessero incuriositi, che se ne andassero col desiderio di scoprire di più, di investigare. Ci sono tante cose che vorrei dalle mie opere ma sono cosciente che quello che voglio è molto più di quanto un’ opera possa effettivamente fare. Vorrei che lo spettatore si sentisse stimolato, in qualche maniera, a mettersi in gioco e farsi domande; vorrei che lasciasse la mostra più curioso di quando vi è entrato.

Esce dagli schemi Lorella. Non si focalizza su un unico punto di vista. Il suo girovagare di città in città, le sue interazioni sociali con culture diverse hanno contribuito a plasmare la sua mente ed anima in maniera plastica, a 360°.

“Quello che cerco di fare nei miei lavori è creare uno spazio che evada i sistemi normativi che dominano la nostra società. Vorrei creare visioni che mostrino realtà da differenti punti di vista, che mostrino anche realtà contrastanti, che si contraddicano. Perché penso che l’essere umano sia stato già per troppo a lungo devoto a questa idea di superiorità ed esclusività tipicamente umanistica, tralasciando cosi la ricchezza di un mondo assai più complesso e infinito di quello che abbiamo creato per noi stessi come razza”

Insomma, la società, l’essere umano, il mondo sono ancora da scoprire nella loro totalità; e la ricerca di tale scoperta va affrontata da più punti di vista, evadendo da schemi classici e/o stereotipati?

“Vorrei riuscire a minare l’antropocentrismo che sta alla base del pensiero occidentale, l’idea di una gerarchia, completamente arbitraria, che pone l’uomo in una posizione di superiorità rispetto al resto del vivente”.

Quando si dice la classica “apertura mentale”, che si riflette su temi cari a Lorella, quali “l’Animale’ e “l’Altro”, passando attraverso riflessioni sul linguaggio e come questo giochi un ruolo fondamentale nella creazione di strutture che configurano la nostra immagine del mondo e concetto di reale.

Un’artista talentuosa e poliedrica, alla continua ricerca della prossima scoperta. Perché la vita, nel caso in cui ce ne fossimo dimenticati, è anche e soprattutto questo.

Le prossime scoperte di Lorella?

“Ho una serie di progetti in cantiere che preferisco non dire fino a che non saranno confermati e sicuri (e forse anche un po’ per scaramanzia). Un progetto del quale sono particolarmente entusiasta è una spedizione di tre settimane a cui prenderò parte in maggio, attraverseremo l’Amazzonia peruviana, durante il quale collezionerò materiale per un progetto di animazione che voglio realizzare e a cui sto pensando già da parecchio tempo”.

Signore e signori: Lorella Paleni. Decisamente Off.

Boum!Bang!

Lorella Paleni

Peintures de rêves.

Julien Foulatier / 11 février 2013

Visiblement, il n’y a ni d’avant, ni d’après, dans les œuvres de Lorella Paleni. Il y a plutôt un « pendant », moment critique au cours duquel les souvenirs resurgissent et les rêves prennent vie. Une sorte de chaos mental, de recueil d’expériences sensorielles et de no man’s land de la logique où, de superpositions en transparences, tout devient vrai et faux simultanément.

Faites d’étranges croisements entre des fragments d’images, les scènes exécutées à la peinture à l’huile par Lorella Paleni gardent en effet tout leur mystère et ne vous racontent que ce que vous voudrez bien y voir. Ici, pas de narration, pas d’espace-temps, pas de repère géographique. Et ce ne sont certainement pas les titres choisis par l’artiste pour qualifier ses œuvres qui vous permettront de trouver votre route.

Ce voyage tout en contrastes est à l’image du parcours de cette jeune peintre. Née en 1986 dans la petite ville de Casazza en Italie, elle fait ses études à l’Académie des beaux-arts de Venise jusqu’en 2010 et part s’installer à New York et Berlin où elle alterne aujourd’hui résidences et expositions.

Influencée par le Caravage et Bacon, elle se dit également proche de l’allemand Matthias Weischer, artiste chez lequel on retrouve ce goût pour l’imbrication des intérieurs et des extérieurs et où le rêve grignote parfois la réalité jusqu’à la rendre illisible. On pourrait également rapprocher le style de certains des portraits plus « classiques » de Lorella Paleni à celui du peintre américain Hernan Bas et voir dans ses œuvres se déroulant dans une sorte d’espace mental une touche surréaliste à la Delvaux. Mais Lorella Paleni ne veut pas d’étiquette. D’ailleurs, un seul mot ne suffirait pas à résumer son univers qui navigue entre figuration et abstraction.

Ses créations, l’artiste les prépare grâce à des collages d’images et des dessins qu’elle assemble pour, par la suite, pouvoir mieux les déconstruire et les désarticuler. Ces manipulations, ces dissections, l’artiste dit également les mener pour mieux comprendre le monde et avoue ensuite laisser toute sa place à l’improvisation et à la chance qui viennent donner à ses toiles cette impression d’imprévu et d’aléatoire onirique.

Lorella Paleni parle également de son travail en évoquant la matérialisation par l’image du moment très précis pendant lequel, en sortant du sommeil, notre esprit encore embrumé mélange fantasmes et souvenirs. Ce moment pendant lequel nos idées ne sont pas encore claires et où nous sommes comme jetés dans le monde, plus fragiles, plus vulnérables et peut-être plus perméables. Ses hallucinations peintes pourraient ainsi être le résultat d’une pensée désordonnée et désorientée, au croisement entre la fin du rêve et le début de la réalité.

Les œuvres de Lorella Paleni sont donc autant de portes volontairement ouvertes sur l’inconscient, mais également autant de portes volontairement fermées prématurément pour que ses images ne puissent être décortiquées et mises à nu. Et c’est ainsi que la magie continue.

Artparasites magazine _ STUDIO VISIT: LORELLA PALENI

Shaking The Hands Of A Painter

Berlin, 13.05.2013

Article by Jovanny Varela-Ferreyra

Join us at the Berlin studio of Italian painter Lorella Paleni for a conversation on the power of paintings to reveal our animal instincts and how the violence inherent in art can also spark love.

“One wants a thing to be as factual as possible and at the same time as deeply suggestive––or deeply unlocking––of areas of sensation other than simple illustrations of the object that you set out to do. Isn’t that what all art is about?” – Francis Bacon with David Sylvester

Shaking the hands of a painter is a tricky maneuver because you never know where her hands have been. When you shake the hand of a businessperson, you can be sure they’ve been conducting business, the same way that you can be sure the hands of a nurse have been nursing and the hands of a thief have been stealing. But when you shake the hands of a painter, you cannot be sure where her hands have been; you cannot be so sure because the answer is always more complex than simply “painting.” So when Lorella Paleni greeted me with her firm handshake at the door of her studio, you can bet I was hesitant.

My ambivalence comes from the realization that paintings are never only paintings. Some people paint windows: frames from where to experience or peek into a different reality. Others paint hammers: tools with which to bring about change. Still others paint mirrors: reflective surfaces from which to better understand the self. And others only paint love letters: containers of devotion. When confronted with the question of whether her paintings were windows, hammers, mirrors or love letters, Paleni, without hesitation or third thoughts replied "windows." "Ah, gotcha," I thought to myself, "I have shaken the hand of a window cleaner."

Looking Through The Window

I can see the reason for answering windows: sometimes her paintings become frames that open up into exterior scenes or peek into interior spaces. For example, there’s a painting in her studio that features a seminude male figure washing his face with what looks more like paint than water. Simultaneously, the painting also displays light blue drips on its surface, which also appear more like paint than water. This piece, Lorella tells me, is one of her favorites––or the one in her studio that she’s more satisfied with.

To my surprise, her paintings began to appear both as windows and mirrors: when you stand in front of a window inside a lit space as you stare into the darkness outside, you may have noticed that, to avoid a complete reflection, you have to stand close enough to the window in order to see the outside through the silhouette of your figure. This is how Paleni’s paintings appeared to me: a space between the inside and the outside bridged by the self. Our conversation then turned to the idea of experiencing paintings as “events.” She tells me that she wishes to bring the viewer to a state free from conscious thought yet full of presence. A place where one feels more than one thinks; where one sees more than one looks and where one is both present and absent simultaneously. You know the feeling: it’s like staring at your reflection in the water––a conflation of the surface material, the self and time. “It’s about creating a moment that feels timeless,” she says.

The Pink Rhinoceros In The Room

One of the most noticeable characteristics about Paleni’s windows and mirrors is her deployment of animal imagery. Fawns, pigs, birds, whether literal or symbolic, populate her work. But the one that sparked my interest the most was the a little painting in the corner of the room with the pink rhinoceros and a circus trainer. It must have been the relationship between the animal and the human constructed the artist that attracted me: rhinoceros can never possibly be trained against their instincts, can they?

“People tend to be fascists with animals,” Lorella mentioned earlier in our conversation. “We expect them to always be at our service and follow our living standards.” And it was staring at this pink rhinoceros that her words began to sink in. I saw myself connected physiologically to the circus trainer but psychologically and emotionally to the rhinoceros. It was here that Lorella Paleni’s paintings felt no longer as windows or mirrors but a bit more like hammers, capable of changing the viewer. I myself became empathetic towards both the human and the animal, trapped in the “event” of her painting.

Perhaps her works have actually always been hammers, as her paintings are not as clean and clear like windows. Furthermore, they maintain a rather violent force that is difficult to describe in written language. “I think any act of creation is violent,” she tells me, “It has to be, no?” Without a doubt. Destruction and creation are complementary forces in which you can’t have one without the other. If Picasso taught us anything is that any act of creation is first an act of destruction.

Lorella and I firmly shook hands again as I left her studio. There was no longer any hesitation as to where her hands had been. On the contrary, a new ambivalence overcame me: where will her hands go from here? She wasn't a window cleaner; her windows proved to be reflective enough to be mirrors, which in turn were shattered by hammers that destroyed as much as they created. Maybe, just maybe, "windows" was her trick answer to my trick question. Perhaps she will go back into her studio and continue doing what she's been doing all along: writing love letters. After all, every act of creation is always an act of love, isn't it?